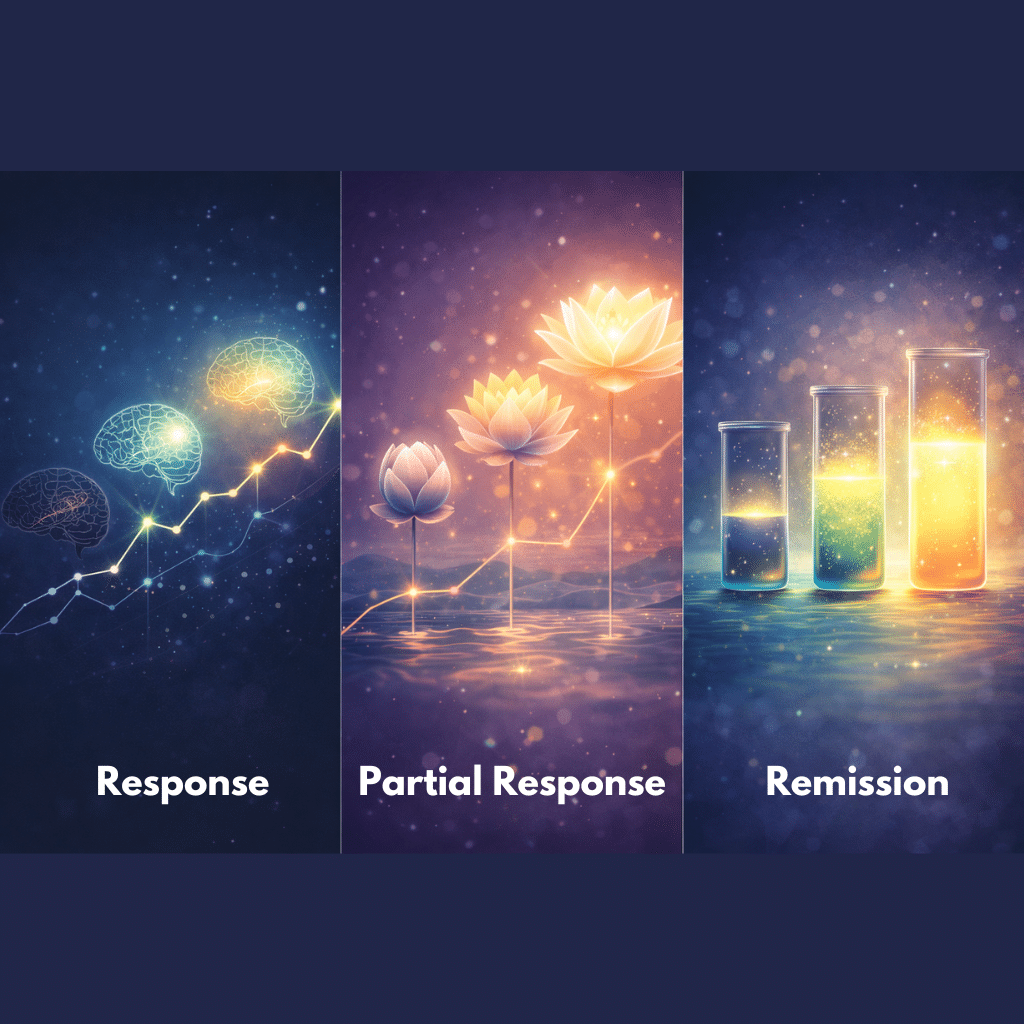

Many people starting ketamine treatment for depression hear words like “response” or “remission” early in the process, although the meaning behind these labels may not feel obvious. Clinicians rely on them because they turn symptom change into something measurable and comparable over time. That structure helps patients see patterns that might be harder to notice in day-to-day life.

This article walks through what each term means, how progress is measured in ketamine therapy, and why these milestones matter when shaping a long-term plan for care.

Defining the Benchmarks

Clinicians use these labels to describe how much a person’s scores improve on tools like the PHQ-9 or MADRS. By measuring symptoms before and throughout ketamine treatment for depression, they can track changes in a consistent, comparable way over time.

A “response” describes a meaningful drop in symptoms. In the 2024 Ganoczy et al. study from the VA Health System, researchers defined response as a 50 percent or greater improvement in PHQ-9 scores. Their real-world group of 215 patients in the VA health system reached that threshold at a rate of 26 percent by week six. That number helps show how response marks a significant shift rather than a small lift in mood.

A “partial response” sits one step earlier. The VA team did not give a special label to this group, but their figures show the idea clearly. If 26 percent reached full response and 15 percent reached remission, many fell into the middle, improving but not yet hitting the 50 percent mark. Clinicians usually view that kind of change as important because it signals the treatment is moving in the right direction.

Remission is the point where symptoms fall into the minimal or near-absent range. In the same VA study, remission required a PHQ-9 score of 5 or less, and 15 percent of participants reached that level by week six. It is common for clinics to treat remission as the main goal because it aligns with better functioning and lower relapse risk.

How Progress Is Measured in Ketamine Therapy

Clinicians follow progress across a ketamine treatment series to capture trends, not just a single good or bad day. They usually begin with a baseline score, often the PHQ-9, then repeat it at set intervals as infusions continue. That routine gives them a consistent way to notice early improvement and check whether the change lasts as sessions are spaced out or adjusted.

The VA study reflects this kind of monitoring. Participants showed their first major changes at six weeks, and those improvements stayed similar at 12 and 26 weeks. That pattern illustrates why repeated measurement matters: A single good week is not the full story.

Alongside the numbers, clinicians pay attention to daily functioning, relationships, and the way a person moves through their routine. Symptoms can drop on paper, but functioning tells them whether life is getting easier outside the clinic.

Why These Distinctions Guide Treatment

Different stages of improvement point clinicians in different directions, and those distinctions matter more than people often expect. They influence how a care team shapes the next phase of ketamine therapy and how a patient understands their own momentum.

For “Response”

When someone reaches a response, the treatment has shown enough strength to keep going. The VA study helps illustrate what that looks like over time: Veterans who improved early did not stop treatment; they continued a tapering schedule, eventually averaging 18 infusions across a year. Early weeks were busier, but the pace slowed as symptoms settled.

That gradual spacing is common in practice because it protects the progress already made without asking patients to maintain an unsustainable rhythm. A response can also signal that it is a good moment to fold in psychotherapy or other supports, especially for people using ketamine for depression as part of a broader plan.

For “Partial Response”

Partial response can feel murky from a patient’s perspective, yet it often carries good news. The VA data showed 15 percent reached remission at six weeks, which means most people improved somewhere short of that point.

Clinicians usually see this middle ground as workable. It may lead them to adjust dose, timing, or bring in another layer of care rather than change course completely. The key idea is that movement is happening and that movement can be strengthened.

For “Remission”

Once someone reaches remission, the treatment goal shifts. CMS guidance highlights remission as the point where functioning improves and relapse risk drops, so the focus moves toward preservation rather than big reductions.

In ketamine treatment, it can look like slower booster schedules paired with supportive behaviors or therapy. Holding steady becomes the aim. The work is about protecting the improvements that got the person there, not forcing symptoms below an already stable range.

Realistic Expectations and the Journey to Wellness

Progress rarely moves in a straight line, and most patients do not reach remission immediately. The VA findings show that both response and remission take time, with response at 26 percent and remission at 15 percent by week six. Those numbers remind people that improvement can arrive in stages: partial response, then response, then remission if treatment continues to work in their favor.

Partial response deserves space in the conversation because it marks momentum. Even a moderate drop in symptoms can create enough relief for someone to reengage with daily life, and those changes often make greater improvement possible.

Charting Your Course: From Measurement to Management

Response, partial response, and remission serve as practical, grounded tools for understanding progress in ketamine treatment. They take a subjective experience and give it shape, helping clinicians tailor each step to what the evidence shows. When patients understand these terms, they can talk through decisions with more confidence and clarity.

If you are considering ketamine for depression or are already in treatment and want help understanding what your progress means, we can walk through it with you. Our team at Zeam uses these benchmarks to personalize each plan, track improvement with care, and support long-term stability. Contact us today in Sacramento, Folsom, or Roseville, to talk about your next steps and how we can help you move toward remission.

Key Takeaways

- Clinical progress in ketamine treatment is measured, not guessed.

Clinicians rely on standardized symptom scales like the PHQ-9 to track change consistently over time, allowing treatment decisions to be based on data rather than isolated impressions.¹ - “Response” typically means a 50% or greater reduction in depressive symptoms.

In large real-world studies, response is defined as a meaningful drop in symptom scores that signals the treatment is working and worth continuing. This milestone often guides tapering and maintenance planning.¹ - “Partial response” reflects meaningful improvement, even if full criteria are not met.

Many patients improve without immediately reaching response or remission thresholds. Clinicians treat partial response as momentum, often adjusting dosing or supportive care rather than abandoning treatment.¹ - “Remission” means symptoms have fallen into a minimal range, not just improved.

CMS quality measures define remission as a PHQ-9 score ≤5, reflecting both symptom relief and improved daily functioning. Reaching remission shifts treatment goals toward stability and relapse prevention.¹ - Progress in ketamine therapy often happens in stages, not all at once.

Data from supervised ketamine programs show that response and remission rates increase over time, reinforcing the importance of patience, monitoring, and individualized treatment pacing.¹

Citations

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Depression Remission at Twelve Months (CMS159v6).

https://ecqi.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/ecqm/measures/CMS159v6.html